Life With A Capital ‘L’

“A thief is only there to steal and kill and destroy. I came so they can have real and eternal life, more and better life than they ever dreamed of” (John 10:13 MSG).

The good life. We all want it. But we don’t know where to find it.

The greatest temptation, to borrow from the Ballad of Jed Clampett, is to equate having the good life with having the right goods.

Is it found in black gold—Texas tea? Will we only experience the life of our dreams when we are sitting in swimmin’ pools with movie stars?[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”But it is the real high road of life; it is only on the way of love, whose paths are described in the Sermon on the Mount, that the richness of life and the greatness of man’s calling are opened up.”–Pope Benedict XVI[/perfectpullquote]

The gospels tell us that Christ came so that we may experience the “abundant life,” or, as Ronald Allen puts it, “Life with a capital L.”[1] Even for us who believe this powerful truth, there is a yawning disconnect with how we tend to experience the world. “Jesus’ idea of the blessed life and our idea of the blessed life have almost nothing in common,” writes Randy Harris.[2] Christ connects the words “blessed”, “fortunate”, and “happy” not with the rich, powerful, satisfied, and well-fed, but with the poor and humble, the mourning and the hungry. Against the Hollywood trend of “love ‘em and leave ‘em”, Jesus calls for fidelity in marriage. Contrary to what many consider advertising genius and “good business sense,” Christ tells us to never engage in verbal manipulation, or make grand claims about mundane things in order to get people to do, buy, or believe something. Instead of offering “good political sense” about protecting yourself against one’s dreaded enemies, Christ calls the good life one in which anger, hatred, defensiveness, and retaliation gives way to love, service, and generosity.

The Sermon on the Mount seems so absurd. Unless, of course, it’s true. Share on XIn short, we are called to love the person more than the product, more than performance, and more than profitability. It seems so absurd.

Unless, of course, it’s true.

As we prepare ourselves for hearing the Sermon on the Mount, let this profound challenge from Pope Benedict XVI rattle our cages:

“But now the fundamental question arises: Is the direction the Lord shows us in the Beatitudes and in the corresponding warnings actually the right one? Is it really such a bad thing to be rich, to eat one’s fill, to laugh, to be praised? Friedrich Nietzsche trained his angry critique precisely on this aspect of Christianity. It is not Christian doctrine that needs to be critiqued, he says, it is Christian morality that needs to be exposed as a ‘capital crime against life.’ And by ‘Christian morality,’ Nietzsche means precisely the direction indicated by the Sermon on the Mount.

‘What has been the greatest sin on earth so far? Surely the words of the man who said “Woe to those who laugh now”?’ And, against Christ’s promises, he says that we don’t want the kingdom of heaven. ‘We’ve become grown men, and so we want the kingdom of earth.’

Nietzsche sees the vision of the Sermon on the Mount as a religion of resentment, as the envy of the cowardly and incompetent, who are unequal to life’s demands and try to avenge themselves by blessing their failure and cursing the strong, the successful, and the happy. Jesus’ wide perspective is countered with a narrow this-worldliness—with the will to get the most out of this world and what life has to offer now, to seek heaven here, and to be uninhibited by any scruples while doing so.

Much of this has found its way into the modern mind-set and to a large extent shapes how our contemporaries feel about life. Thus, the Sermon on the Mount poses the question of the fundamental Christian option, and, as children of our time, we feel an inner resistance to it—even though we are still touched by Jesus’ praise of the meek, the merciful, the peacemakers, the pure. Knowing now from experience how brutally totalitarian regimes have trampled upon human beings and despised, enslaved, and struck down the weak, we have also gained a new appreciation of those who hunger and thirst for righteousness; we have rediscovered the soul of those who mourn and their right to be comforted. As we witness the abuse of economic power, as we witness the cruelties of a capitalism that degrades man to the level of merchandise, we have also realized the perils of wealth, and we have gained a new appreciation of what Jesus meant when he warned of riches, of the man-destroying divinity Mammon, which grips large parts of the world in a cruel stranglehold. Yes indeed, the Beatitudes stand opposed to our spontaneous sense of existence, our hunger and thirst for life. They demand ‘conversion’—that we inwardly turn around to go in the opposite direction from the one we would spontaneously like to go in. But this U-turn brings what is pure and noble to the fore and gives a proper ordering to our lives.

The Greek world, whose zest for life is wonderfully portrayed in the Homeric epics, was nonetheless deeply aware that man’s real sin, his deepest temptation, is hubris—the arrogant presumption of autonomy that leads man to put on the airs of divinity, to claim to be his own god, in order to possess life totally and to draw from it every last drop of what it has to offer. This awareness that man’s true peril consists in the temptation to ostentatious self-sufficiency, which at first seems so plausible, is brought to its full depth in the Sermon on the Mount in light of the figure of Christ.

We have seen that the Sermon on the Mount is a hidden Christology. Behind the Sermon on the Mount stands the figure of Christ, the man who is God, but who, precisely because he is God, descends, empties himself, all the way to death on the Cross. The saints, from Paul through Francis of Assisi down to Mother Teresa, have lived out this option and have thereby shown us the correct image of man and his happiness. In a word, the true morality of Christianity is love. And love does admittedly run counter to self-seeking—it is an exodus out of oneself, and yet this is precisely the way in which man comes to himself. Compared with the tempting luster of Nietzsche’s image of man, this way seems at first wretched, and thoroughly unreasonable. But it is the real high road of life; it is only on the way of love, whose paths are described in the Sermon on the Mount, that the richness of life and the greatness of man’s calling are opened up.”[3]

[1] Ronald J. Allen, “The Surprising Blessing of the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-9),” in David Fleer & Dave Bland (eds.), Preaching the Sermon on the Mount: The World It Imagines (St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press, 2007), p. 88.

[2] Randy Harris, Living Jesus: Doing What Jesus Says in the Sermon on the Mount (Abilene, TX: Leafwood, 2012), p. 31.

[3] Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth, Vol 1: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, Trans. Adrian J. Walker (New York: Doubleday, 2007), p. 97-99.

EARLIER POST IN THIS SERIES

The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1

THE NEXT POST IN THIS SERIES

New Things To Love: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 3

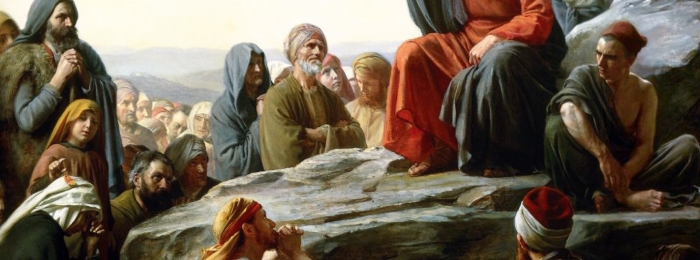

photo credit: Sermon on the Mount by Carl Heinrich Bloch, 1890

Nathan Guy believes the passionate pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty culminates in Jesus Christ. He received formal training in philosophy, theology, biblical studies, and cultural & political ethics from Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE. He lives in Florence, Alabama, where he serves as President of Mars Hill Bible School.

[…] POSTS IN THIS SERIES The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1 Life with a Capital ‘L’: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 2 New Things To Love: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part […]

[…] Lesson 2: Life With a Capital ‘L’ […]