Healthy Theology 7: Thinking Well

“Two things can save the world, thought and prayer; but the trouble is the people who think don’t pray, and the people who pray don’t think.” – Bruce Marshall, Satan and Cardinal Campbell

“ARE THERE NO SINS OF INTELLECT?”

Some people are naturally curious–always skeptical, inquisitive, and probing. Others seem not so burdened. There is nothing inherently virtuous or vicious about such temperaments. There is a tradition which states St. Augustine—who challenged every view he ever held, and wrote treatises to defend every position he ever thought—had a mother who was his opposite. Monica held to a simple faith, never doubting the why, the how, or the ends of her faith. Both of these approaches to faith are held in high esteem in Christian tradition.

Perhaps you are a Monica type of Christian: faith comes easy for you. That is nothing to scoff at; in fact, it’s praiseworthy.

But what if you take after Augustine in temperament? If so, how do you react to the questions that fill your mind? Do you respond like Augustine, or do you intentionally ignore the rigors of Christian intellectual curiosity, afraid where it might lead? Do you follow the pursuit of knowledge, or do you seek to silence the doubts in your soul—hoping to hold to whatever truths please the senses? In The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis imagines a conversation between two souls after death, discussing the dangers of such neglect:

“This is worse than I expected. Do you really think people are penalized for their honest opinions? Even assuming, for the sake of argument, that those opinions were mistaken.”

“Do you really think there are no sins of intellect?”

“There are indeed…But honest opinions fearlessly followed—they are not sins.”

“I know we used to talk that way. I did it too until the end of my life…It all turns on what are honest opinions…Let us be frank. Our opinions were not honestly come by. We simply found ourselves in contact with a certain current of ideas and plunged into it because it seemed modern and successful. At College, you know, we just started automatically writing the kind of essays that got good marks and saying the kind of things that won applause. When, in our whole lives, did we honestly face, in solitude, the one question on which it all turned: whether after all the Supernatural might not in fact occur? When did we put up one moment’s real resistance to the loss of our faith?”

“…The point is that they were my honest opinions, sincerely expressed.”

“…[A] drunkard reaches a point at which (for the moment) he actually believes that another glass will do him no harm. The beliefs are sincere in the sense that they do occur as psychological events in the man’s mind. If that’s what you mean by sincerity they are sincere, and so were ours. But errors which are sincere in that sense are not innocent.”

“Are there no sins of intellect?” Could it be that some errors of thought and judgment, though sincere, “are not innocent?” This is a problem for Christians and non-Christians alike. Immanuel Kant challenged his peers with the Enlightenment refrain “Dare to Know!” But he did not discover such daring on his own; his Christian upbringing likely instilled such a response.

MAY GOD BE GLORIFIED IN THE LIFE OF THE MIND

In an earlier series called “Preparing for Theology,” I suggested that discipleship includes loving God with all of our minds and that true, submissive faith is faith seeking understanding (a phrase borrowed from St. Anselm). As J. P. Moreland observes, Christian tradition has long challenged believers to be people of substance and depth, believing what is true in an effort to develop a well-informed character. This calls us to practice the virtue of reasoned reflection and to have a studious spirit.

Consider one form of the famous “prayer before study” (in Latin here) attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas:

Creator of all things, true source of light and wisdom, origin of all being, graciously let a ray of your light penetrate the darkness of my understanding.

Take from me the double darkness in which I have been born, an obscurity of sin and ignorance.

Give me a keen understanding, a retentive memory, and the ability to grasp things correctly and fundamentally.

Grant me the talent of being exact in my explanations and the ability to express myself with thoroughness and charm.

Point out the beginning, direct the progress, and help in the completion. I ask this through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

In this beautiful prayer, Aquinas calls for God to be glorified even in our intellectual life and pursuits.

THE POSSIBILITY OF A CHRISTIAN INTELLECTUAL

Several universities (such as the LSE) claim the motto “rerum cognoscere causas” which means “to know the causes of things.” The quote is attributed to the poet Virgil; however, the ancient author of Ecclesiastes lived by a similar motto: “I applied mine heart to know, and to search, and to seek out wisdom, and the reason of things” (Ecclesiastes 7:25 KJV). Imagine such a goal in life: to understand the how, where, and why of all things that can be known! Surely the Christian in pursuit of God in His fullness is engaged in such a search. Christian tradition has long challenged believers to be people of substance and depth, believing what is true in an effort to develop a well-informed character.

It is no surprise, and no coincidence, that much of intellectual history is pursuit of both God and “the good.” Every branch of learning involves a search for truth, and many facets of Christian theology seek to engage the mind in asking challenging questions concerning ethics and philosophy. We may ask what is good, what does it mean to be good, and what decision would count as good in a given situation. We may inquire what is the nature of being, the nature of truth, or the nature of justice. In terms of Christian beliefs, we sense the need to go beyond what is orthodox and what is heresy—to a consideration of the deep and intricate mysteries surrounding even the simplest as well as most profound truths. It is incorrect to think that because God remains shrouded in mystery it is unhealthy to seek after him using the tools and resources He has placed at our disposal. For example, to ask philosophical questions about theological claims (as this website will attempt to do, Lord willing) is to join a long, rich tradition of “feeling after God” in an effort not only to know Him (in whatever way one can), but to adequately reflect on what it means to be known by Him. To quote Francis Bacon:

Let no man out of a weak conceit of sobriety, or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain that a man can search too far or be too well studied in the book of God’s Word, or in the book of God’s works; divinity or philosophy; but rather, let men endeavor an endless progress of proficiency in both.

Forgive the archaic language and gender-specific language (it was 1605 after all). But what Bacon says is true for every Christian in pursuit of healthy theology. Seeking to know is seeking understanding, and seeking understanding–guided by faith and respect for the Holy One–is seeking wisdom. As the ancient Proverb goes (published, in English, around the same time as Bacon): “Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding” (Proverbs 4:7 KJV).

Resources For Further Reflection

Book: JP Moreland, Love Your God With All Your Mind

Book: Alister McGrath, The Passionate Intellect: Christian Faith and Discipleship of the Mind

Article: Dallas Willard, “A Thinking Faith“

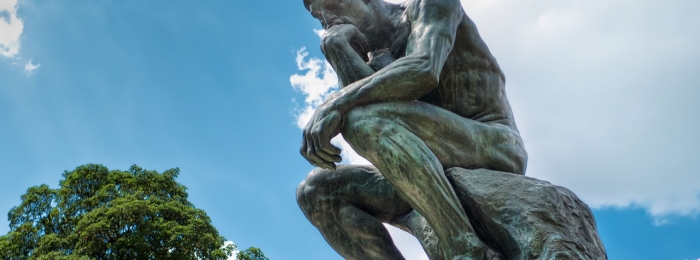

(photo: Rodin’s “The Thinker.” Credit: Mustang Joe)

Nathan Guy believes the passionate pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty culminates in Jesus Christ. He received formal training in philosophy, theology, biblical studies, and cultural & political ethics from Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE. He lives in Florence, Alabama, where he serves as President of Mars Hill Bible School.

This Post Has 0 Comments