New Things To Love

“What do you want?”

These are the first words of Jesus in the Gospel of John (John 1:38). What a challenging question! And to you and me, the reader, he asks it again and again–in a number of ways.

- To a man in need of sight (Mk 10:51; Lk 18:41), and to disciples who struggled with spiritual vision (Mt 20:32; Mk 10:36), Jesus asks: “What do you want me to do for you?”

- To a man who lay sick, unaware of the power (and the life that comes about as a result of that power) awaiting him, Jesus asks: “Do you want to be made well?” (John 5:6).

Look down deep inside yourself. How would you answer the Lord? What is that you really, really want?

To answer that question, it might help to know where to look. The ancients spent a lot of time trying to locate the center of our wills. Perhaps you know the Egyptians, before embalming and entombing notables, would place most internal organs in special jars (for use in the afterlife). They kept the heart, of course, but the brain—well, the brain they threw out. What use do you have for that?

Before we laugh too hard, consider that—at least in one sense—this story rightly causes us to pause and reconsider where we think our desires chiefly reside.

We usually associate the heart with deep emotion; but Paul aims at the gut. Paul appeals to our “bowels of mercy” because, for those of his day, the intestines were the seat of emotion. The “heart”, more often, was the seat of reason. That is why the proverb teaches “guard your heart; for out of it flow the well springs of life.”

And when they went looking for the seat of the will—where rationality and emotion combine with one’s deepest intentions, attitude, and willingness to follow through—they often spoke of the “mind.”

Nehemiah highlights what good can be done with a singular mind in the right direction. The people of God rebuilt the walls of the city in just 40 days, “for the people had a mind to work” (Neh 4:6). But Babel shows the chilling results of a singular mind in the wrong direction. God confounds their language to keep them from uniting to dominate, control, and, ultimately, to destroy. As one version puts it, God is concerned that “nothing that they have a mind to do will be impossible for them” (Gen 11:6).

Unity of “mind” reflects unity of purpose, intention, and desire. Have you ever been “of one mind” toward a certain goal? Have you ever wanted just one thing? I know Robert Browning said “a man’s reach should always exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” But what if the one thing you desire was the heavenly life of eternity, made real in the present? This describes our Lord Jesus Christ.

- “I desire to do your will, my God” (Psalm 40:8)

- “Teach me to do your will, for you are my God. May your good Spirit lead me on level ground” (Psalm 143:10)

- “Here I am, I have come to do your will, my God” (Hebrews 10:7&9)

- “Your kingdom come, your will be done” (Matt 6:10).

- “If its not possible for this cup to be taken away unless I drink it, may your will be done” (Matt 26:42).

So when Paul claims that Christians “have the mind of Christ” or challenges us to “let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus”, he’s not talking about how high is your intellect, or how well your reasoning, how quickly you are moved to tears, or how moved you are by emotional appeals. He is asking about what you want; he is challenging what you desire; he is questioning what you will. Paul wants us to want what Christ wants.

And so does Christ.

There is a strong link between the mind and the heart, the will and the decision. After all, how many of us can say we know what we should desire, but have a hard time staying on track? In the end, our actions reveal what our soul deeply craves.

Show me what you do—habitually, instinctively, routinely, and willingly—and I’ll show you what you intentionally or unintentionally desire.[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”Education is love formation. When you go to school it should offer you new things to love.”–David Brooks[/perfectpullquote]

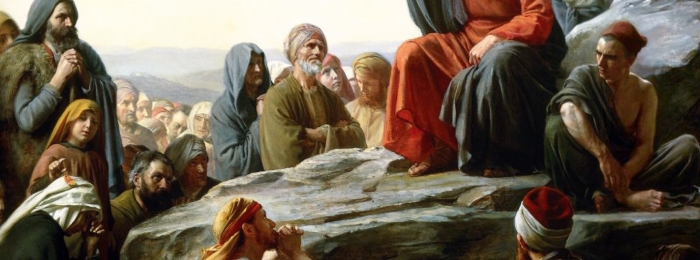

Here is where the Sermon the Mount comes in. According to Charles Talbert, many Christians through the centuries have interpreted the Sermon as being primarily (or exclusively) about ethical decision-making: what to do, or not to do, and how to analyze a situation, and choose the right method in order to do the good and avoid the wrong. But what if the Sermon also has to do with (or, possibly, primarily has to do with) character formation: becoming the kind of person whose intentions, motivations, and dispositions lead us to properly choose the good and avoid the wrong?[1]

This approach has much to commend it. After all, there are lots of approaches to ethical decision-making, many of which are found in Scripture, and no one of them is exclusively ‘Christian’ in nature.[2] Sometimes decisions are rooted in duty to commands (Ex 20:13-17; Lev 19:18; Matt 5:27-28, 38-42; Rom 13:8-10), sometimes with regard to one’s goals or consequences (Deut 28:1-2, 15; Matt 6:2-6, 14-18; Rom 13:4-5), and sometimes centered in the self-actualization of virtue (Lev 21:7; Deut 14:1-2, 21; Matt 5:14-16a; Rom 6:11-13). All three approaches appear in the Sermon on the Mount! Sometimes biblical authors, like Paul, will use all three approaches interchangeably (see Eph 5:3-10).[3] To illustrate, consider how “goals,” “commands,” and “virtues” all appear in 1 Timothy 1:5: “The goal of this command is love, which comes from a pure heart.”

In addition, the Sermon on the Mount prescribes practices—habits, or rituals—like praying, fasting, and giving. These things do not directly lend themselves to “ethical decision making;” that happens indirectly—since we shouldn’t do these things “like the hypocrites do.” But learning and practicing spiritual habits, like Daniel Larusso’s learning to “sand the floor” and “paint the fence,” not only help us to develop skills, but also help us to become a new kind of person—one for whom such habits define a way of life.

Pennington says we should read the Sermon on the Mount with this question constantly on our lips: how does this teaching, question, or practice shape my character and make me a better person?[4] Dallas Willard rightly calls us to raise our vision higher than the bar for entering heaven, or the process for receiving forgiveness. “Being saved” is not the only issue, says Willard; an equally important issue is this: “who have you become?”[5]

Who, indeed. Because the Sermon on the Mount calls us to reflect the character of Christ himself. To become—as Lewis once put it—“little Christs”: not just in terms of making good decisions, but becoming the kind of person who desires the things God would have us choose.

Let us become the kind of person who desires the things God would have us choose. Share on XWe have a fancy phrase for this: “spiritual transformation.” And people outside the circle of Christian faith see the importance—and great need—for something like it.

David Brooks is an op-ed columnist for the New York Times. As far as I know, he does not confess to being a Christian. In his book, The Road to Character, Brooks describes two kinds of virtues that people seek in life: the resume virtues, and the eulogy virtues. Most people spend their time at school, and most of their lives, in pursuit of learning and living the resume virtues – those things that show you are competent at your job, can best the competition, can climb the social ladder, and can out-maneuver everyone else in a kill-or-be-killed world. Instead, writes Brooks, when we take a minute to think about the fleeting nature of life, we will begin to reflect on the eulogy virtues, those things people will hopefully say about us when we are gone. At our funeral, will they speak of how much money we made, or how cut-throat we could be? We would hope, of course, that they would speak of our humility and kindness, our bravery, honesty, and faithfulness—those things usually associated with spiritual maturity.

“If you live for external achievement,” writes Brooks, “years pass and the deepest parts of you go unexplored and unstructured. You lack a moral vocabulary. It is easy to slip into a self-satisfied moral mediocrity. You grade yourself on a forgiving curve. You figure as long as you are not obviously hurting anybody and people seem to like you, you must be OK. But you live with an unconscious boredom, separated from the deepest meaning of life and the highest moral joys. Gradually, a humiliating gap opens between your actual self and your desired self.”[6]

What Brooks discovered is what St. Augustine said long ago: you are (and will become) what you love. Brooks explains what this means:

“We become what we love because only love compels action. We don’t become better because we acquire new information but because we acquire better loves. We don’t become what we know. Education is a process of love formation. When you go to school it should offer you new things to love.”[7]

Brooks hits on a truly spiritual note: the answer to our troubles is not to find a new mantra, or a 5-step process for behavior modification. There needs to be a transformation from the inside-out, in which we don’t simply learn how to constantly say “no” to our desires, but have our desires changed into things to which the wise and spiritual person would say “yes”!

The eminent church historian, Robert Wilken, couldn’t agree more.

“I am convinced,” writes Wilken, “that the study of early Christian thought has been too preoccupied with ideas. The intellectual effort of the early church was at the service of a much loftier goal than giving conceptual form to Christian belief. Its mission was to win the hearts and minds of men and women and to change their lives.”[8]

Motivated in this way, Wilken set about writing The Spirit of Early Christian Thought as a new kind of church history: one centered on the goals or ends to which Christian ideas pointed, to the kind of people we were supposed to become as a result of embracing Christian truths. In other words, to discuss what it means to grow into what we love.

School should give us “new things to love,” challenges Brooks. “The church gave men and women a new love,” responds Wilken, “Jesus Christ, a person who inspired their actions and held their affections.”[9] Call it the “school of Christ.” The voice of wisdom is simply echoing St. Augustine’s prayer to God, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless, until it rests in you.[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“The church gave men and women a new love, Jesus Christ, a person who inspired their actions and held their affections.”–Robert Louis Wilken[/perfectpullquote]

In the end, we can summarize the problem in very simple terms: there is a tug of war between the mind of Christ and the mind that is centered on the self. It’s a tale of two different loves. Brooks diagnoses the problem: for many in our culture today, what it means to pursue a worthy goal is simply this: to be true to yourself (without knowing what you were made for) by pursuing your hearts desire (a heart that doesn’t know what it ought to desire). We live with a social media culture where—to borrow a phrase—“to be ‘liked’ matters even more to us than being well-liked,” and certainly more than being admired for virtues that stand opposed to what most people ‘like.’[10] And what is the result? For Brooks, it means that we have lost our ability to empathize, and instead of loving people and using things, our default position is precisely the opposite.

Not coincidentally, that was Augustine’s line, too. And the culture he was describing is 1600 years old than ours.

“If we are going to discern what really matters,” writes James K. A. Smith, “the place to start is by attending to our loves.”[11] The teaching and practices of Christ and the church are designed to make us into better lovers. And we need to pay attention to it.

Why? Because we have bought the cultural narrative hook, line, and sinker. “Define yourself by your unintentional desires. Consider how you aren’t getting what you want, and make getting it the cause of your life. See everyone and everything through the lens of your political views, your pet project, or your unique take on the world. And if anyone—including Christ and His church—gets in the way and won’t let you pursue it, go alone or find a community that will.”

On the other side, of course, is the call to self-denial. A call to adopt new things to love. Read a famous passage in an unfamiliar translation: According to Galatians 5:22, the Spirit produces fruit in our hearts and lives, and the goal here is to get rid not just of our outward desires, but our inward condition: for “those who belong to Christ have crucified their old nature with all that it loved.”

At some point, the language of self-help, self-esteem, and self-expression must give way to a greater foundation: what our new love demands. For the Christian, Christ-centered love is how one comes to know and discern what is best (Philippians 1:9-11), and wisdom is shown in a good life, “by deeds done in humility,” rather than the “unspiritual” and “demonic” wisdom of the world displayed through harboring “bitter envy and selfish ambition” in our hearts (James 3:13-15). Listen carefully as James continues:

“For where you have envy and selfish ambition—[the kind of things often aiding the resume virtues]—there you find disorder and every evil practice. But the wisdom that comes from heaven is first of all pure; then peace-loving, considerate, submissive, full of mercy and good fruit, impartial and sincere. Peacemakers who sow in peace reap a harvest of righteousness” (James 3:16-18).

Did you catch that list? Pure (of heart), merciful, peacemakers. James is describing the kind of person who, contrary to the resume-virtue-seeking world around us, Jesus calls “blessed”, “fortunate”, and “happy”…in the Sermon on the Mount.

Brooks seeks desperately to find an antidote to the challenge set before us, some way to reorient ourselves. What does Brooks suggest we do? Well, what do you think? Learn some intellectual truths, develop virtuous habits, and participate in meaningful rituals. Develop a code of life that emphasizes humility over pride, and acts of charitable giving over self-indulgence. And above all, to submit to a larger community that demands these things of us.

And here we come full circle. Wilkins begins his book with these words: “The Christian religion is inescapably ritualistic (one is received into the church by a solemn washing with water), uncompromisingly moral (‘be ye perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect’), and unapologetically intellectual (given a reason for the hope that is in you).”[12] That is, Christians make it our aim to do right things, think right things, and practice healthy habits. And we do this together as a community of love. You show me what you intellectually believe, how you morally behave, and what rituals you practice, and I’ll tell you what you love.

We are made to love, and only the love of God will provide rest for restless hearts. Christians through the centuries have seen the best way to love God is through loving pursuit, learned and practiced in the communal life of the church. This involves reading texts, holding orthodox beliefs, learning moral habits, and engaging in personal and church-wide rituals. This involves the intellect, the spirit, and the body: which is what it means to love God with all your heart, soul, and mind. The church believes that what you think, and what you do, work together to help define who you are, and what you will become. And the inner process of transformation of character—to make us into better people, living a fuller life—is what Christian teach and church life are all about.

But we are not Christian simply because we do these things, think these things, and practice these things. As the old saying goes, standing in a garage does not make one an automobile. No, at first we may very well work feverishly through the motions (that is not always entirely bad). But ultimately, by the Spirit of God, we do, think, and practice these things because we think and act with the mind of Christ. This is who Christ is, and so this is what “little Christs” think and do. His love compels us, which means we do as His Spirit increases our desire, and become what we love.

[1] Charles H. Talbert, Reading the Sermon on the Mount: Character Formation and Ethical Decision Making in Matthew 5-7 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2004), pp. 27-31.

[2] Scot McKnight lists various approaches and concludes that the Sermon on the Mount doesn’t fit neatly into any of these. See Scot McKnight, Sermon on the Mount, The Story of God Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013), pp. 13-14.

[3] All examples and passages given in Talbert, pp. 27-31.

[4] Jonathan T. Pennington, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing: A Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2017), p. 16.

[5] Dallas Willard, “The Need For Spiritual Formation,” Workshop on Spiritual Formation, lesson 1. Since his lecture extends halfway into lecture 2, see the following two lectures (the citation can be found during lecture 2): https://web.archive.org/web/20150322183855/http://www.bethinking.org/human-life/spiritual-formation; https://web.archive.org/web/20150606035039/http://www.bethinking.org/human-life/spiritual-formation/2-case-studies.

[6] David Brooks, “The Moral Bucket List,” The New York Times, April 11, 2015.

[7] David Brooks, The Road To Character (New York: Random House, 2015), p. 211.

[8] Robert Louis Wilken, The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), p. xiv.

[9] Wilken, p. xv.

[10] Rebecca Mead, “David Brook’s Search For Meaning,” The New Yorker, May 27, 2015.

[11] James K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Brazos Press, 2016), kindle edition.

[12] Wilken, p. xiii.

EARLIER POSTS IN THIS SERIES

The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1

Life with a Capital ‘L’: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 2

THE NEXT POST IN THIS SERIES

A Change of Desire: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 4

photo credit: Sermon on the Mount by Carl Heinrich Bloch, 1890

Nathan Guy believes the passionate pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty culminates in Jesus Christ. He received formal training in philosophy, theology, biblical studies, and cultural & political ethics from Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE. He lives in Florence, Alabama, where he serves as President of Mars Hill Bible School.

Thank you for sharing this!

Thanks, Tim.

[…] Lesson 3: New Things to Love […]