The Cost Of Apprenticeship

Allow me to take stock of where we are. To help us get our bearings, I am introducing some key “starting points” for understanding the Sermon on the Mount. First we saw that happiness is found in Jesus Christ, but involves a radically different way of seeing the world (and ourselves). Christ came to offer abundant life–the life of the Kingdom. Sometimes our world shows signs of recognizing the power and attraction of the Kingdom (especially as they realize how empty our cultural narratives are), but for the most part the call of Christ stands in stark contrast to the pull of dominant forces around us. Since we are caught up in the vortex of this struggle, we need (and Christ promises to give us) not just new things to believe, or new practices to perform, but new things to love, which involves a Spirit-directed and Spirit-transforming change of desire. So far, then, we’ve learned that the best way to approach the Sermon on the Mount is to see what life is like for those desiring the Kingdom of love–where hearts are no longer restless, since they rest in God.

Today I would like to deepen the discussion. A change of desire will inevitably yield a change of direction, attitude, and action. We will, in fact, become different people with a different purpose. It’s time to talk about discipleship in the context of love and desire.

THE PROBLEM

In an earlier post, I noted that the word “disciple” occurs almost 300 times in the New Testament, while the term “christian” appears just 3 times. In fact, writes Dallas Willard, “the very term Christian was explicitly introduced in the New Testament…to apply to disciples.”[1] I was first made aware of this by reading Willard’s earlier book, The Spirit of the Disciplines, where he makes the point emphatically: “The New Testament is a book about disciples, by disciples, and for disciples of Jesus Christ.”[2]

But the church, sadly, often is not. “There is a sense of shame,” writes John Stott; “too often what [people] see in the church is not counter-culture but conformism, not a new society…but another version of the old society… not life but death.”[3]

The German theologian and martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer diagnosed the problem in his own day as “cheap grace,” which he described as “the enemy of the Church,” and defined as a grace that requires no actual change in me: “Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.”[4]

According to Willard, the diagnosis remains the same. “It is now generally acknowledged,” writes Willard, “that one can be a professing Christian and a church member in good standing without being a disciple. There is, apparently, no real connection between being a Christian and being a disciple of Jesus.”[5]

And the problem is just as severe.

Nondiscipleship is the elephant in the church. It is not the much discussed moral failures, financial abuses, or the amazing general similarity between Christians and non-Christians. These are only effects of the underlying problem. The fundamental negative reality among Christian believers now is their failure to be constantly learning how to live their lives in The Kingdom Among Us. And it is an accepted reality. The division of professing Christians into those for whom it is a matter of whole-life devotion to God and those who maintain a consumer, or client, relationship to the church has now been an accepted reality for over fifteen hundred years. And at present…that long-accepted division has worked its way into the very heart of the gospel message. It is now understood that to be a part of the ‘good news’ that one does not have to be a life student of Jesus in order to be a Christian and receive forgiveness of sins.[6]

Willard’s prefers a synonym for this “cheap grace”: “costly faithlessness.”[7]

According to Stott, the failure of the contemporary church is a tragic one.

It is urgent that we not only see but feel the greatness of this tragedy. For insofar as the church is conformed to the world, and the two communities appear to the onlooker to be merely two versions of the same thing, the church is contradicting its true identity. No comment could be more hurtful to the Christian than the words, ‘But you are no different than anybody else.’[8]

THE DEMAND

In truth, God has always called out a peculiar people for himself; a holy people—called to look different, act different, think different, and live differently than the world from which we came. Stott calls this “the essential theme of the whole Bible from beginning to end.”[9] What was true and central in his call to Israel (Lev. 18:3) remains true and central in Christ’s Sermon on the Mount: “Do not be like them” (Matt 6:8).

It is the same call to be different. And right through the Sermon on the Mount this theme is elaborated. Their character was to be completely distinct from that admired by the world (the beatitudes). They were to shine like lights in the prevailing darkness. Their righteousness was to exceed that of the scribes and Pharisees, both in ethical behaviour and in religious devotion, while their love was to be greater and their ambition nobler than those of their pagan neighbours.[10]

“There is no single paragraph of the Sermon on the Mount in which this contrast between Christian and non-Christian standards is not drawn,” writes Stott. “It is the underlying and uniting theme of the Sermon; everything else is a variation of it.”[11]

Thus the followers of Jesus are to be different—different from both the nominal church and the secular world, different from both the religious and the irreligious. The Sermon on the Mount is the most complete delineation anywhere in the New Testament of the Christian counter-culture. Here is a Christian value-system, ethical standard, religious devotion, attitude to money, ambition, life-style and network of relationships—all of which are totally at variance with those of the non-Christian world. And this Christian counter-culture is the life of the kingdom of God, a fully human life indeed but lived out under the divine rule.[12]

THE GRACIOUS INVITATION

But we must not forget that the call to discipleship is an unbelievably good and gracious invitation! This beautiful truth, however, can be so hopelessly lost in the delivery.

Its possible to speak of discipleship as grace in the barest way possible: “You deserve death, but God has offered a gauntlet for the few, the proud, the spiritual marines; if those few tributes can get past the gladiators at the gates, and the guards in the tower, then God will give them a ticket to heaven.” But this would be to completely misunderstand the situation.

If “cheap grace” is the ditch on the left, merit-based achievement salvation is the ditch on the right.

“‘Only those who believe obey’ is what we say to that part of a believer’s soul which obeys, and ‘only those who obey believe’ is what we say to that part of the soul of the obedient which believes,” writes Bonhoeffer. “If the first half of the proposition stands alone, the believer is exposed to the danger of cheap grace, which is another word for damnation. If the second half stands alone, the believer is exposed to the danger of salvation through works, which is also another word for damnation.”[13]

Hear the call to discipleship. Hear it as a gracious invitation to apprenticeship. Hear it as the loving call to the blessed life. Share on XBonhoeffer goes on to give us four reasons to avoid the ditch on the right. First, all talk of discipleship takes its cue from our beautiful Master, who offered forgiveness even as he hung on the cross. “The mercy and love of God are at work even in the midst of his enemies,” writes Bonhoeffer. “It is the same Jesus Christ, who of his grace calls us to follow him, and whose grace saves the murderer who mocks him on the cross in his last hour.”[14]

Happy are they who know that discipleship simply means the life which springs from grace, and that grace simply means discipleship. Happy are they who have become Christians in this sense of the word. For them the word of grace has proved a fount of mercy.[15]

Second, discipleship is liberating. It frees us from ourselves, closes off the forces that threaten to wound us, and opens us to the abundant life for which we are destined, for which we were made!

When the Bible speaks of following Jesus, it is proclaiming a discipleship which will liberate mankind from all man-made dogmas, from every burden and oppression, from every anxiety and torture which afflicts the conscience. If they follow Jesus, men escape from the hard yoke of their own laws, and submit to the kindly yoke of Jesus Christ.[16]

Third, discipleship means joy!

[I]f we answer the call to discipleship, where will it lead us? What decisions and partings will it demand? To answer this question we shall have to go to him, for only he knows the answer. Only Jesus Christ, who bids us follow him, knows the journey’s end. But we do know that it will be a road of boundless mercy. Discipleship means joy.[17]

Finally, discipleship involves Divine enablement. The power to follow in the footsteps of Jesus is given to us by Christ himself through the Holy Spirit. “The commandment of Jesus is not a sort of spiritual shock treatment,” writes Bonhoeffer. “Jesus asks nothing of us without giving us the strength to perform it. His commandment never seeks to destroy life, but to foster, strengthen and heal it.”[18]

IN PURSUIT OF THE KING

Discipleship, then, is a loving response to a gracious invitation that brings blessing into our lives. It is the pursuit of the blessed life, since it is the pursuit of the Blessed One.

To help bring out this point, Dallas Willard speaks of the disciple as an apprentice to Jesus. “A disciple, or apprentice, is simply someone who has decided to be with another person, under appropriate conditions, in order to become capable of doing what the person does or to become what that person is.”[19] “Living as an apprentice with Jesus in The Kingdom Among Us” involves being “the constant student and co-laborer with Jesus in all the details” of your life.[20]

Think of the change that would occur in our churches (and in ourselves) if we thought of discipleship as apprenticeship?

For one thing, it would help confirm our identity. Willard points out that “in our religious culture…there is a long tradition of doubting, or possibly even of being unable to tell, whether or not one is a Christian”—mainly in places where identity-shaping definitions were reduced to one question: “whether or not one was going to ‘make the final cut.’”[21]

But apprenticeship offers a healthier approach. “There is no good reason why people should ever be in doubt as to whether they themselves are his students or not,” writes Willard, because “being a disciple, or apprentice, to Jesus is a quite definite and obvious kind of thing.”[22] Just think about whether one knows where they work, or for what profession they are preparing, or who is the teacher shaping their lives.

People who are asked whether they are apprentices of a leading politician, musician, lawyer, or screenwriter would not need to think a second to respond. Similarly for those asked if they are studying Spanish or bricklaying with someone unknown to the public. It is hardly something that would escape one’s attention. The same is all the more true if asked about discipleship to Jesus.[23]

We probably struggle with identity-shaping definitions because we recognize our failures. But being a disciple and being a better or worse disciple than we were yesterday are two different conversations altogether! Willard reminds us that a person learning a trade or working in a business would have no problem identifying themselves as an apprentice in that craft. “But, if asked whether they are good apprentices of whatever person or line of work concerned, they very well might hesitate.”[24] He continues: “Asked if they could be better students, they would probably say yes. [But] all of this falls squarely within the category of being a disciple, or apprentice.”[25]

All of this language is in the service of answering the great problem we addressed at the beginning. Willard makes the point:

The greatest issue facing the world today, with all its heartbreaking needs, is whether those who, by profession or culture, are identified as ‘Christians’ will become disciples—students, apprentices, practitioners—of Jesus Christ, steadily learning from him how to live the life of the Kingdom of the Heavens into every corner of human existence.[26]

To help churches become apprentice workshops, Willard urges them to develop a “curriculum for Christlikeness”—one centered around, for example, the Sermon on the Mount. “Imagine, if you can,” writes Willard, “discovering in your church letter or bulletin an announcement of a six-week seminar on how genuinely to bless someone who is spitting on you.”[27]

I can imagine that very thing, thanks to Lee Daniel’s The Butler. I remember watching that emotional and memorable lunch-counter scene, where the movie shoots back and forth between the staged protest in the restaurant, and the grueling preparation it took to get them there.

“You know that ya’ll can’t sit here.”

“We would like to be served please.”

“This is unprecedented,” declares a voice, harking back to their earlier preparation, “what we are talking about. But it needs a patience that none of us have ever seen. We are organized. We have a leader with every group. We have lookouts, and local phone numbers with ambulances ready. And when one wave comes off that lunch counter, what follows? A whole ‘nother wave of students sitting at that lunch counter, blowing their minds.”

When one student expresses discomfort hurling such insults, the leader responds “you came here to get yourself prepared, and to get her prepared.”

The scene shifts back to the lunch counter. A mob forms outside.

Coming into the restaurant, the hate-filled racists treat the men and women at the lunch counter mercilessly. They smack their heads, pull their clothes, scream in their faces, pour food all over them. And, yes, spit in their face.

But the men and women sitting at the lunch counter endure it all. Because they were prepared.

When you read the Sermon on the Mount, you are reading an outlined curriculum for Christlikeness. The “hardness” in the message speaks to the seriousness of the cause. We are apprentices to Jesus—and Jesus prepares us for the cross.

SINGLE-MINDED OBEDIENCE

The gracious call to apprenticeship is free, but, as Bonhoeffer famously said, it is not cheap. “[G]race is costly because it calls us to follow…it is costly because it costs a man his life, and…above all, it is costly because it cost God the life of his Son…and what has cost God much cannot be cheap for us.” But “it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ…it is grace because it gives a man the only true life…[and] above all, it is grace because God did not reckon his Son too dear a price to pay for our life, but delivered him up for us.” And, because it is “costly grace,” “grace and discipleship are inseparable.”[28]

Remove the call to die, and you cut the golden thread uniting the disciple with the high calling of Christ in His Sermon on the Mount. Share on XThis is how we begin (or continue) the Christian counter-culture. The people of God will be different in every aspect of their lives through “single-minded obedience” to the demands of costly grace.[29]

“Only the obedient believe,” writes Bonhoeffer, and “only he who is obedience can believe.”[30] “The man who disobeys cannot believe, for only he who obeys can believe.”[31] A few pages earlier, he clarifies why this is the case. “Only he who believes is obedient, and only he who is obedient believes…For faith is only real when there is obedience, never without it, and faith only becomes faith in the act of obedience.”[32] In short, discipleship is characterized by a “single-minded obedience” to Christ. “Christianity without discipleship,” writes Bonhoeffer, “is always Christianity without Christ.”[33]

And obedience to the call and lead of the Savior cannot be piecemeal; he demands every part of you. “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die,” Bonhoeffer famously wrote.[34] The center of our religion is not a beautiful flower or calming mantra; it is a cross—the same one which every disciple is called to bear.

The obedience of the cross means self-denial, detachment from all that we love more than and instead of Jesus Christ.

The cross is laid on every Christian. The first Christ-suffering which every man must experience is the call to abandon the attachments of this world. It is that dying of the old man which is the result of his encounter with Christ. As we embark upon discipleship we surrender ourselves to Christ in union with his death—we give over our lives to death. Thus it begins; the cross is not the terrible end to an otherwise god-fearing and happy life, but it meets us at the beginning of our communion with Christ.[35]

To those who stand gazing at the Messiah, questioning his call, counting the cost, and deliberating how much of themselves they are willing to risk, Bonhoeffer offers this rebuke: “You are disobedient, you are trying to keep some part of your life under your own control…Tear yourself away from all other attachments, and follow him.”[36]

Christ forms a wedge between us and our former way of life.“We must face up to the truth,” writes Bonhoeffer, “that the call of Christ does set up a barrier between man and his natural life…By virtue of his incarnation he has come between man and his natural life. There can be no turning back, for Christ bars the way.”[37]

The call of Christ, then, is a call to die to our desires and loves that war against the soul. “In fact,” Bonhoeffer continues, “every command of Jesus is a call to die, with all our affections and lusts. But we do not want to die, and therefore Jesus Christ and his call are necessarily our death as well as our life.”[38]

Remove the call to die, and you cut the golden thread uniting the disciple with the high calling of Christ in His Sermon on the Mount. As Stanley Hauerwas once remarked, “The Sermon does not appear impossible to a people who have been called to a life of discipleship that requires them to contemplate their death in the light of the cross.”[39]

Hear the call to discipleship. Hear it as a gracious invitation to apprenticeship. Hear it as the loving call to the blessed life. And recognize the high demand of a life that goes counter to the spirit of our age.

We can only achieve perfect liberty and enjoy fellowship with Jesus when his command, his call to absolute discipleship, is appreciated in its entirety. Only the man who follows the command of Jesus single-mindedly, and unresistingly lets his yoke rest upon him, finds his burden easy, and under its gentle pressure receives the power to persevere in the right way. The command of Jesus is hard, unutterably hard, for those who try to resist it. But for those who willingly submit, the yoke is easy, and the burden is light.[40]

[1] Dallas Willard, The Divine Conspiracy: Rediscovering Our Hidden Life In God (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), p. 282.

[2] Dallas Willard, The Spirit of the Disciplines: Understanding How God Changes Lives (San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1988), p. 258.

[3] John R. W. Stott, The Message of the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5-7): Christian Counter-Culture (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1978), p. 16.

[4] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship, rev & unabridged, trans. R. H. Fuller and Imgard Booth (New York: Macmillan, 1959), p. 36.

[5] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 291. “It is now universally conceded today that you can be a Christian without being a disciple” (p. 282).

[6] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 301.

[7] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 301.

[8] Stott, p. 17.

[9] Stott, p. 17.

[10] Stott, p. 18-19.

[11] Stott, p. 19.

[12] Stott, p. 19.

[13] Bonhoeffer, p. 58.

[14] Bonhoeffer, p. 32.

[15] Bonhoeffer, p. 47.

[16] Bonhoeffer, p. 31

[17] Bonhoeffer, p. 32

[18] Bonhoeffer, p. 31.

[19] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 282.

[20] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 291.

[21] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 281.

[22] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 281.

[23] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 282.

[24] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 282.

[25] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 282.

[26] Dallas Willard, The Great Omission: Reclaiming Jesus’ Essential Teachings on Discipleship (San Francisco, CA: HarperOne, 2014).

[27] Willard, The Divine Conspiracy, p. 313.

[28] Bonhoeffer, p. 37-38.

[29] Bonhoeffer, see esp. pp. 69-75.

[30] Bonhoeffer, p. 55 & p. 39.

[31] Bonhoeffer, p. 57.

[32] Bonhoeffer, p. 54.

[33] Bonhoeffer, p. 50.

[34] Bonhoeffer, p. 79.

[35] Bonhoeffer, p. 79.

[36] Bonhoeffer, p. 59 & p. 60.

[37] Bonhoeffer, p. 85.

[38] Bonhoeffer, p. 79.

[39] Stanley Hauerwas, “Living the Proclaimed Reign of God: A Sermon on the Sermon on the Mount,” Interpretation 47 (April 1993), p. 154.

[40] Bonhoeffer, p. 31.

EARLIER POSTS IN THIS SERIES

The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1

Life with a Capital ‘L’: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 2

New Things To Love: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 3

A Change of Desire: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 4

THE NEXT POST IN THIS SERIES

Calling All Neurotics: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 6

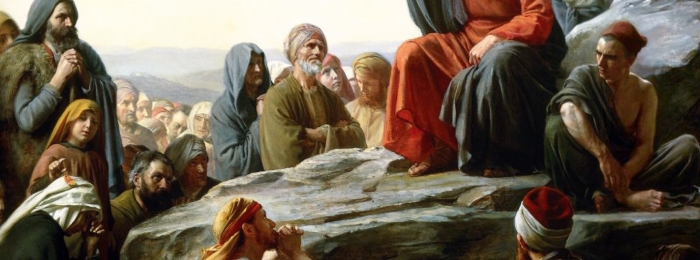

photo credit: Sermon on the Mount by Carl Heinrich Bloch, 1890

Nathan Guy believes the passionate pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty culminates in Jesus Christ. He received formal training in philosophy, theology, biblical studies, and cultural & political ethics from Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE. He lives in Florence, Alabama, where he serves as President of Mars Hill Bible School.

This Post Has 0 Comments