The Complete Art Of Happiness

[Today I begin a series of blog posts reflecting on the Sermon on the Mount. I am spending the summer reading this fascinating and challenging text for three reasons: 1) to prepare for my Christian Ethics course this fall, 2) to prepare for a Sunday night sermon series at Cloverdale, and 3)…to be fully transparent…to resist the forces of culture and to let God set my soul in the way of happiness. I pray these posts will be as much of a blessing to you as the study has been (and continues to be) for me.]

“[It] has been a blockbuster bestseller. It spent more than two years on the New York Times bestseller list, including hitting #1, has sold more than 1.5 million copies, and has been published in more than thirty languages.”[1]

So reads the blurb advertising a highly sought-after book. What is the subject matter that garners such interest? How to be happy.

Gretchen Rubin titled her book The Happiness Project: Or, Why I Spent A Year Trying to Sing in the Morning, Clean My Closets, Fight Right, Read Aristotle, and Generally Have More Fun. That “reading Aristotle” bit in the subtitle was intentional on her part; Aristotle thought that learning what happiness is, and doing whatever it takes to find it, is the secret to the meaning of life.

Think of it as our “ultimate” goal. The endpoint of every road we intentionally choose to travel. Why do we go through the pain, the sweat, the tears? Endure the years of pressure, experience the daily grind, or take the nervous leap? You may name some intermediate good (think “the perfect house, the perfect car, or the perfect job”), but even those things are in pursuit of something less tangible but more important: a sense of happiness.

The problem is that no matter how hard we try, happiness seems to elude us. The wise and rich king Solomon spent years chasing after happiness, only to conclude that it cannot be found in wealth, fame, or legacy—the right job, the right spouse, the right retirement plan or the right vacation (Ecclesiastes 1:14; 2:3-11). I think we know—deep down inside—that happiness does not come pre-packaged with gadgets or glam.

We know that happiness is more than just a positive attitude, making lemonade out of the world’s lemons. That is, of course, a nice way of thinking, but one that is made available to a truly happy person, not one that makes a truly happy person.

We also know that happiness is not the same thing as pleasure, and shouldn’t be confused with it. When given the choice to live in blissful ignorance, or to know the truth, we often opt for the latter. There are lots of things that appear to bring pleasure into our lives which we avoid for other, deeper reasons. We will go through pain, and avoid what “feels good” in the moment, in order to have long-lasting happiness.

We sense that happiness is not a thing to be bought, or an event to attend; it is, as Rubel Shelly puts it, “a quality of spirit rather than a circumstance created by the right combination of gadgets, bucks, and glammor.”[2] It refers to a quality of life–being and doing–that is not based on how much, or how little one has. Happiness is actively living in a state of blessedness.

Happiness is actively living in a state of blessedness. Share on XWould it surprise you to learn that in the first century of the common era, a sermon began circulating containing the teachings of Jesus Christ, which offers a description of the “blessed,” “fortunate,” or, in some translations, “happy”? John Wesley told his audience that the whole point of Christ coming into the world was “to bless men; to make men happy.” For this reason, Jesus preaches a sermon to begin “his Divine institution, which is the complete art of happiness, by laying down before all that have ears to hear, the true and only true method of acquiring it.”[3]

Imagine that. A sermon given by the Lord himself describing “the complete art of happiness”? You would think such a sermon would be a best-seller and claim millions of disciples.

And you’d be right. Sort of.

There is a reason why this sermon (recorded in Matthew 5-7) is known as the Sermon. “In the indices to the fathers of the first three centuries,” writes Jonathan Pennington, “one will find Matt. 5 is quoted far more frequently than any other, and chaps. 5-7 are quoted far more frequently than any other three consecutive chapters.”[4] In other words, “the Sermon has been the most commented upon portion of Scripture throughout the church’s history.”[5] St. Augustine called it the “charter of the Christian life,” believing it contained all the precepts needed for the formation of a happy, moral, fulfilling life.[6] In early centuries of Christian history, the Sermon served as a primary source for spiritual renewal as well as moral formation.[7] Later Christian writers, including such giants as Luther, Calvin, and Wesley, wrote influential commentaries on the Sermon. It was even one of Ghandi’s favorite texts—one he chastised Christians for neglecting. Indeed, it is far more than a Christian text. Pinckaers pinpoints the wide appeal of the Savior’s words:

There are few passages in Scripture that touch the Christian heart more surely and deeply, or that have a greater appeal for nonbelievers… [T]he Sermon touches non-Christians more deeply and has far greater appeal than any moral theory based on natural law in the name of reason. It is as if the Sermon strikes a human chord more ‘natural’ and universal than reason by itself can ever do.[8]

If the Sermon is so good, so rich, and so aimed toward our own ultimate desire for a life of true happiness…what’s the catch? There must be a catch. Because the Sermon is often…quite often…highly neglected. “To bless men; to make men happy, was the great business for which our Lord came…[He] therefore begins his Divine institution, which is the complete art of happiness, by laying down…the true and only true method of acquiring it.”–John Wesley

40 years ago, John Stott said “the Sermon on the Mount is probably the best-known part of the teaching of Jesus, though arguably it is the least understood, and certainly it is the least obeyed.”[9] Or as Daniel Doriano updates, “the Sermon on the Mount is perhaps the most beloved, the best known, the least understood, and the hardest to obey.”[10] William Mattison, a virtue-ethicist and philosopher, claims the Sermon has long been neglected among Christian ethicists and moral theologians, is often skipped even by New Testament ethicists, and is missing not only as a text in ethics classes, but as a rule of parenting in most Christian homes.[11]

But the “hardness” factor is not what you might think. Contrary to some popular opinion, Jesus doesn’t actually teach that you have to be a sinless superhuman to do what the Sermon calls us to do. In fact, the entire Sermon takes place within a larger context of grace. In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus has already called people to himself, already spoke of the kingdom of God which is a received gift from our gracious God. In the early 16th century, William Tyndale already saw this point clearly:

All these deeds rehearsed, as to nourish peace, to shew mercy, to suffer persecution, and so forth, make not a man happy and blessed; neither deserveth he reward of heaven; but declare and testify that we are happy and blessed, and that we shall have great promotion in heaven; and certify us in our breasts that we are God’s sons, and that the Holy Ghost is in us: for all good things are given to us freely of God, for Christ’s blood sake and his merits.[12]

Hauerwas insists that we reframe the discussion. Instead of laying out a list of virtues or actions in order to make us happy, Christ calls us into a community of the blessed, and declares “happy are they who find that they are so constituted within the community.”[13]

God’s grace comes first. This is why the Sermon begins with “blessing.” “I’m convinced,” writes Randy Harris, “the world needs the blessing of God in order to practice the words of the Sermon on the Mount.” Randy warns us:

If you try to live out the commands of the Sermon on the Mount without being blessed by God, without feeling loved by God, without knowing that God is holding you close to his side, you’re going to grind away and you’re never going to get there…I believe it’s impossible to live out the Sermon on the Mount if we don’t first understand that we are loved and blessed by God. We all pursue the American dream. We all want what is described as the good life, but Jesus reassures us that the good life is found in unexpected places…The good life, counter-intuitively, is found in places of persecution and even in places of poverty. The good life can be found in these places, too, because God’s love is what produces good life.[14]

But the sermon does challenge us. In the grace of God, and in the love of Christ, the Sermon calls for us to give up the things we most want to keep, and to respond in ways we least want to share. As Pennington puts it, “It’s a call to be a certain way in the world. An invitation to walk a certain way—such a person is happy, flourishing.”[15] It was Chesterton who once said “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.” Richard Hughes brings this point home with a few memorable lines. He notes that the Sermon offers a radical message to the rich, the powerful, and the exploiters. “But the American church does not wish to be radicalized,” writes Hughes, “precisely because, more often than not, we are those rich and powerful exploiters whom the Sermon on the Mount both indicts and convicts.”[16]

The Sermon forces us to come face to face with the character of Jesus—who shows us what it looks like to receive blessed happiness in the presence of Almighty God. As John Stott lovingly writes, the Sermon

depicts the behaviour which Jesus expected of each of his disciples, who is also thereby a citizen of God’s kingdom. We see him as he is in himself, in his heart, motives and thoughts, and in the secret place with his Father. We also see him in the arena of public life, in his relations with his fellow men, showing mercy, making peace, being persecuted, acting like salt, letting his light shine, loving and serving others (even his enemies), and devoting himself above all to the extension of God’s kingdom and righteousness in the world.[17]

Perhaps its for this reason that Pennington claims “[w]ithout exception, one’s reading of the Sermon says much about one’s understanding of Jesus and Christian theology.”[18] The Sermon challenges us to consider how should we view the past (how God has spoken and acted in the history of Israel), how should we live in the present (including religious rituals, acts of piety, and relations with neighbors and enemies), and how should we face the future (with expectations of a better life, and, if so, when and how that better life will be experienced).

In short, the Sermon challenges us at every turn. “When we seek to ‘improve’ the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount,” writes Scot McKnight, “we too often ruin the words of Jesus. There is something vital…in letting the demand of Jesus, expressed over and over in the Sermon as imperatives or commands, stand in its rhetorical ruggedness. Only as a demand do we hear this Sermon as he meant it to be heard; as the claim of Jesus upon our whole being.”[19]

Meanwhile, we join our culture in the rat race to find true happiness. We work very hard, and very long, toward this goal. As the words of Jesus stare us in the face—declaring “blessed, fortunate, and happy are these”—and the Spirit-directed life of Jesus provides a living image of the happy-infused life of God, we continue to walk on by, asking ourselves, “when will I ever find happiness?”

In this series of posts, I will work through some reflections from my summer reading on the Sermon on the Mount. I pray that you, along with me, will internalize the teaching, be challenged by it, and center our understanding of happiness in Christ himself. Let McKnight offer a helpful conclusion for what practicing “the complete art of happiness” looks like:

The happiness of the Beatitudes is not about feeling good but about being good, and being good is defined by Jesus and shaped by one’s relationship with God through him. Being blessed by Jesus may have nothing to do with one’s observable condition in life and everything to do with whether one loves God, loves self, and loves others as the self. That, along with the behaviors that emerge out of that kind of love, makes one blessed.[20]

[1] https://gretchenrubin.com/books/the-happiness-project/about-the-book/

[2] Rubel Shelly, The Beatitudes: Jesus’ Formula for Happiness (Nashville, TN: 20th Century Christian, 1982; repr., 1984), p. 3.

[3] John Wesley, Explanatory Notes upon the New Testament (1754; repr. Salem, OR: Schmul, n.d.), p. 19.

[4] Jonathan T. Pennington, The Sermon on the Mount and Human Flourishing: A Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017), p.3 n.2.

[5] Pennington, pp.2-3.

[6] Augustine, The Lord’s Sermon on the Mount, trans. John Jepson, S.S. (New York: Paulist Press, 1948), i.1.1.

[7] Servais Pinckaers, The Sources of Christian Ethics, trans. Mary Thomas Noble (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1995), pp. 134-135.

[8] Pinckaers, p. 163.

[9] John R. W. Stott, The Message of the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7): Christian Counter-Culture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1978), p. 15.

[10] Daniel M. Doriani, The Sermon on the Mount: The Character of a Disciple (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2006), p. 1.

[11] William C. Mattison III, The Sermon on the Mount and Moral Theology (Cambridge: CUP, 2017), pp. 1 & 4.

[12] William Tyndale, Expositions and Notes on Sundry Portions of the Holy Scriptures, Together with the Practice of Prelates by William Tyndale, Martyr, 1536, ed. Henry Walter (Cambridge: CUP, 1849), p. 228.

[13] Stanley Hauerwas, “Living the Proclaimed Reign of God: A Sermon on the Sermon on the Mount,” Interpretation 47 (April 1993), p. 157.

[14] Harris, pp. 32-33.

[15] Pennington, pp. 51-52.

[16] Richard Hughes, “Dare We Live in the World Imagined in the Sermon on the Mount?”, in David Fleer & Dave Bland (eds.), Preaching the Sermon on the Mount: The World It Imagines (St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press, 2007), p. 45.

[17] Stott, p. 24.

[18] Pennington, pp. 2-3.

[19] Scot McKnight, Sermon on the Mount, The Story of God Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013), pp. 2-3.

[20] McKnight, p. 51.

THE NEXT POST IN THIS SERIES

Life With A Capital ‘L’: Sermon On The Mount–Intro: Part 2

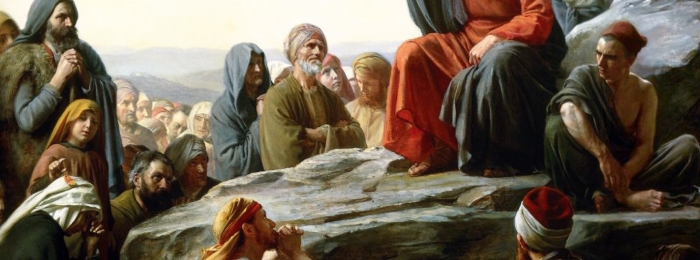

photo credit: Sermon on the Mount by Carl Heinrich Bloch, 1890

Nathan Guy believes the passionate pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty culminates in Jesus Christ. He received formal training in philosophy, theology, biblical studies, and cultural & political ethics from Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE. He lives in Florence, Alabama, where he serves as President of Mars Hill Bible School.

[…] “Lesson 1: The Complete Art of Happiness” (Cloverdale Church of Christ, Searcy, AR, August 26, 2018) [related post] […]

[…] POSTS IN THIS SERIES The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1 Life with a Capital ‘L’: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 2 New Things To Love: […]

[…] some key “starting points” for understanding the Sermon on the Mount. First we saw that happiness is found in Jesus Christ, but involves a radically different way of seeing the world (and ourselves). Christ came to offer […]

[…] Lesson 1: The Complete Art of Happiness […]

[…] FIRST POST IN THIS SERIES ON THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT The Complete Art of Happiness: Sermon On The Mount Intro–Part 1 […]